Macaroni Men; The Original Holiday Wardrobe

Have you ever heard the song Yankee Doodle? Do you remember the opening lines and wonder what it could possibly mean?

“Yankee Doodle went to town riding on a pony, he stuck a feather in his cap and called it macaroni”

To the modern ear it’s a peculiar phrase that doesn’t seem to have any logical meaning, especially in terms of dress history! The origins of this song have been discussed frequently and it is largely associated with the American War of Independence. It was supposedly used to belittle American soldiers[1], with the term ‘Yankee’ being used to mean a ‘country lout’.[2] However, our focus today is why on Earth sticking a feather in your cap would share a name with a type of pasta?!

To find the answer we must travel back to a world of French chateaus, Italian piazzas and Viennese coffee houses, on what became commonly known as a Grand Tour. This term comes from a guidebook written in the 17th Century titled ‘The Voyage of Italy’[3] and quickly became used to describe the journeys taken by the British upper classes from the 16th to 18th Century to absorb the food, fashion and culture of different nations. In fact, the travelling became so popular that that it was viewed by many as an essential part of a rounded education. Amongst those who went were a group of young men who pushed the boundaries of fashion and style in 18th Century Britain and eventually gained the name of ‘Macaroni’.

(Fig. 1) Yankee Doodle Song Print. USA, Date Unknown. The Kennedy Centre.

(Fig. 2) The Basin of San Marco on Ascension Day, Canaletto, 1740. The National Gallery.

Meet the Macaronis

So, who were these macaroni men? The term started appearing in print and publications in the mid to late 1700’s, particularly following David Garrick’s 1757 play The Male-Coquette.[4] They were described in an article in 1772 as a group of men who had brought back an Italian dish called macaroni (quite literally described as “a kind of paste”) and started a dining club in central London. It was here that they swapped ideas about art, “genteel sciences” and fashion. In truth, however, this article questioned their claim to a greater knowledge and culture beyond simply dressing the part![5]

The second half of the 18th Century was a period of great political turbulence both nationally and internationally. The American War of Independence (1775-1783) and the Anglo-French war (1778-1783) were closely followed by the French Revolution (1789-1799), which gave weight to a rejection of many of the ‘foreign’ styles. Therefore, the desire for fancy fashion utilising styles and materials from other nations would have been cause for concern. This is especially significant following the Calico Riots of the early 18th Century, where women wearing imported Calico gowns were attacked for significantly reducing the British textile and weaving trade.[6] In fact, French silk imports were banned in England in 1766 and remained heavily restricted until 1826,[7] so the young men adopting distinctly European clothing would have definitely been viewed with suspicion by the public, as they were bending the rules of acceptable styles and materials.

Furthermore, the style and silhouette of the clothing the Macaronis wore significantly deviated from the contemporary styles in Britain at the time. The British stereotype character of John Bull[8], which was commonly featured in publications like Punch in the 18th Century depicted a very different image of the ideal British male than a Macaroni. John Bull has always been a large, portly and bullish type figure, whilst the Macaronis preferred a more elegant and streamlined image. The Bull vs Macaroni divide resulted in a suggestion that the Eurocentric Macaroni men (during a time of great distrust of Britain’s neighbours) had a weakness of character. They could even be viewed as unpatriotic[9][10] and often they were viewed with great suspicion as a result.

A large portion of the discussions regarding the Macaroni Men centre around gender and sexuality. The period of time when they flourished was certainly a time for men re-evaluating how they presented themselves in terms of masculinity and gender boundaries.[11] Whilst not the focus of this post, it is important to acknowledge this topic as it does have a bearing on how a Macaroni Man might be viewed by society. Questioning a person’s sexuality based on their choice of clothing, something that unfortunately continues to this day, was prevalent at the time, with some social commentaries going as far as questioning a Macaroni’s interest in women altogether.[12] As homosexuality has been part of societal diversity for as long as there has been a society to exist in, one cannot deny that there were some men who may well have found common ground amongst his Macaroni peers, but the choice of clothing doesn’t inherently denote the sexual orientation of a person. Peter McNeil discusses the gender studies of the Macaroni extensively in his book Pretty Gentlemen[13], and to anyone interested in the topic I would highly recommend reading further.

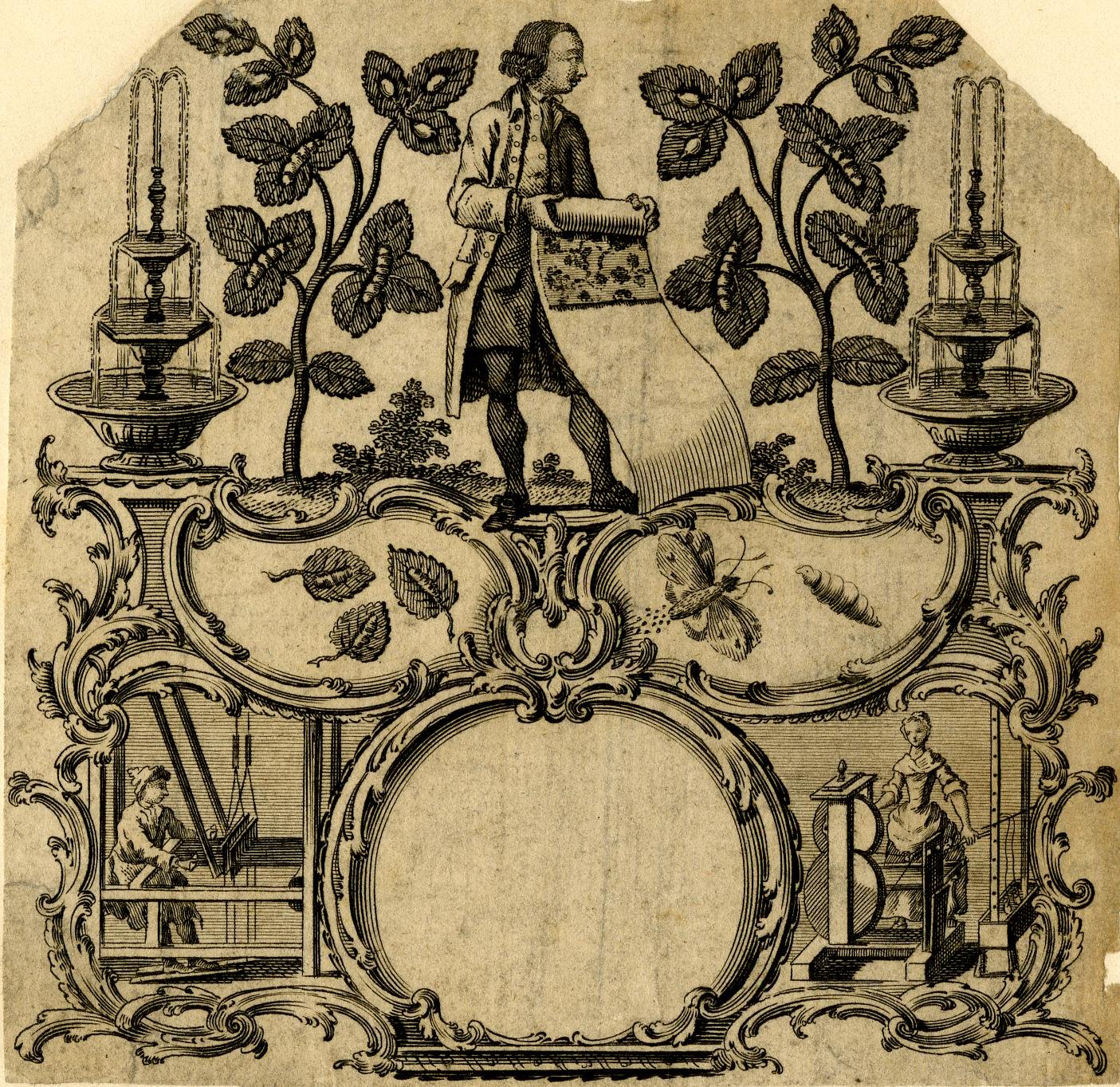

(Fig. 3) Trade Card Print, 1700s. The British Museum.

(Fig. 4) The Contrast (John Bull pictured Right), published by Carington Bowles, c.1783. National Portrait Gallery.

(Fig. 5) Augustus Henry FitzRoy ('The Turf Macaroni'), Mary Darly, 1771. National Portrait Gallery.

Sartorial Choices

But what were these Macaroni men actually wearing that was so controversial? There are several elements to this so let’s start with the ‘unpatriotic’ silhouette we touched on earlier. The three piece suit had developed over the course of the previous century[14], so was still a relatively new idea. The changes happening to style allowed for a degree of self-expression and experimentation which manifested for the Macaroni as a much shorter, slimmer and streamlined appearance than the full skirted frock-coat many men were wearing, which can be seen in many archival examples… and the copious amount of satire at the time!

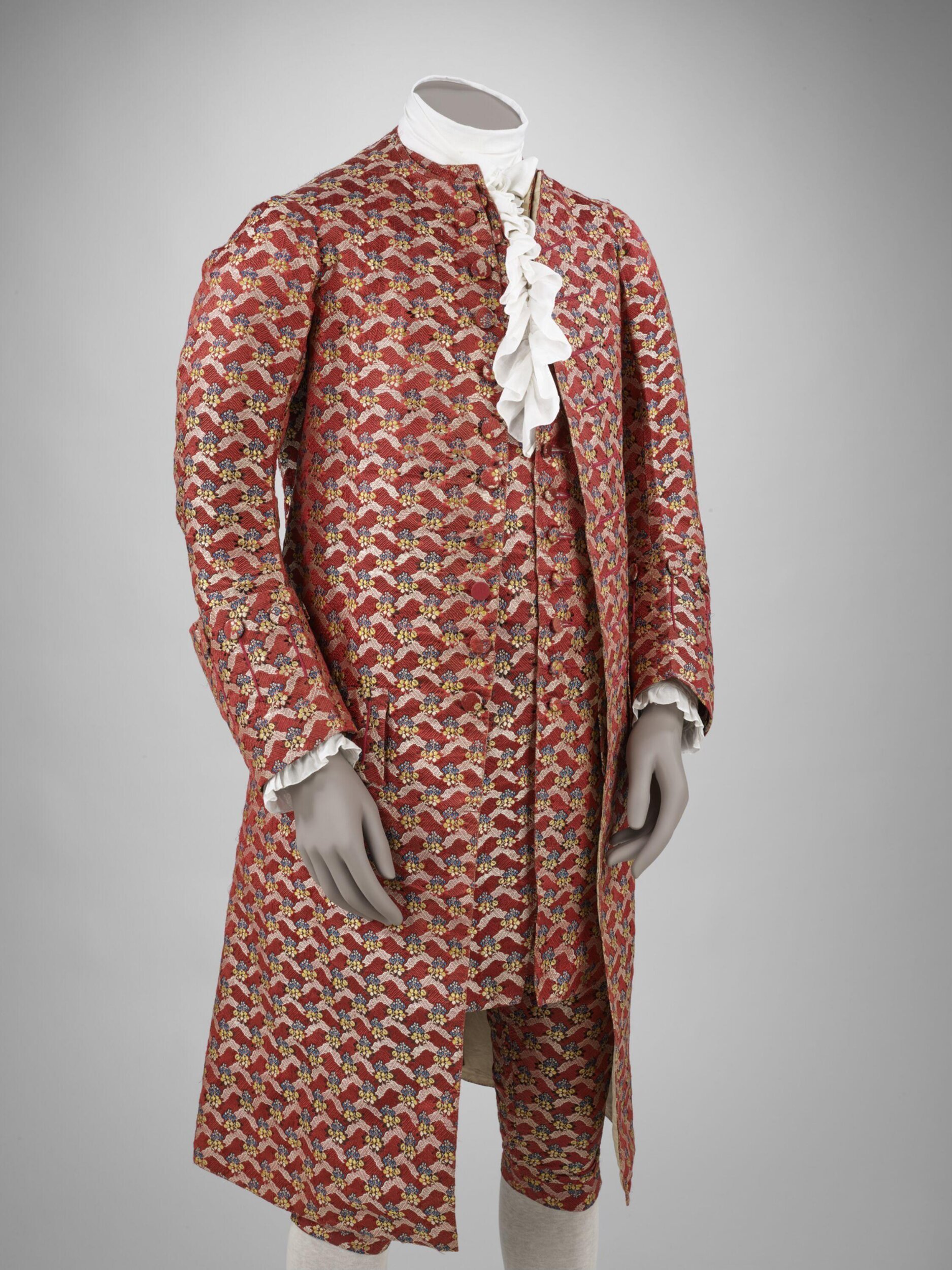

However, the typical choices of garments largely followed the usual building blocks of 18th Century men’s fashion. For the upper body, the Macaroni would begin with a cotton or linen shirt and stock (a starched neckcloth which fastened at the back). Then a waistcoat could be worn, closely followed by a high-collared coat. Pockets in both the waistcoat and outer coat could be functional, or simply decorative to avoid ruining the silhouette.[15] For the lower half, knee-breeches were a must, but could be cleverly cut to emphasise the shape of the Macaroni’s calves, which would be covered in cotton or silk stockings – usually white but there’s certainly evidence for other colours too. [16][17][18]

(Fig. 6) Lord Algernon Percy, 1777-1780. National Gallery of Art.

(Fig. 7) Coat, 1760. Victoria and Albert Museum.

(Fig. 8) Detail of Coat, 1760. Victoria and Albert Museum.

Shoes were a hot topic, especially in the contemporary writings about the macaroni where complaints, again centred around gender values in 18th Century Britain, even went as far as commenting on the men and women of Bath society, which saw women in riding dresses and uniforms whilst the Macaronis “trip in pumps… with parasols over their heads”[19]. Heeled shoes, made popular by the French court and King Louis XIV, came in a variety of colours and decorated with ribbons and buckles. Buckles, either plain or decorative (using paste, glass, or even diamonds![20]) could be made of silver or steel, as the latter had really started gaining popularity in this period.

(Fig. 9) Silver, Gilt and Base Metal Buckles Display Case, 18th-19th Century. Kenwood House.

(Fig. 10) Detail of Paste Buckles Display Case, 18th-19th Century. Kenwood House.

(Fig. 11) Paste Buckles Display Case, 18th-19th Century. Kenwood House.

Whilst the garments were similar to mainstream choices, the colours in clothing was a key element to the Macaroni individuality. They tended towards the brighter scale with pinks, oranges and greens being popular along with blue and red in various shades. Many of these colours were chosen based on fashion from Europe at the time and included silks, cottons and linens with brocade, embroidery and patterns such as spots and stripes.[21][22] Many of the prints we see show how layered the colours and fabrics could be. In a time where the fashion did not necessarily favour dark colours as a rule, but the restrictions on fabric imports and a suspicion of the French courts, this may well have also contributed to an idea of frivolity amongst the Macaroni men.[23]

(Fig. 12) Coat, Unknown, 1760-1770. Victoria and Albert Museum.

(Fig. 13) Lord - or the Nosegay Macaroni, 1773. The British Museum.

(Fig. 14) Portrait of Francis Lind (1734-1802) George Romney, 18th Century. Christie’s.

Other accessories include the 18th Century equivalent to a keyring, known as a chatelaine, which would be hung from the waist of breeches to carry small and dainty accessories, like a decorative watch or keys. More dramatically, swords decorated with ribbons would often be carried by the Macaroni along with a reticule - small bags were far more desirable than a pocket that would stretch out and ruin your silhouette! [24]

Finally, the ‘crowning glory’ of a true Macaroni outfit is the hair - wigs at this time grew taller and developed little curls at the side, which were created using curling rags or papers. Similar to non-Macaroni men’s wigs at the time, they would often be tied at the back but prints and satire indicate they could be more full and decorative than their less fashion-conscious friends. The hair could be caught into a wig bag, which is sometimes described as ‘en bourse’ using Early Modern French, which developed from the Medieval Latin ‘bursa’, meaning ‘bag’ (not to be confused with the current French translation of ‘bourse’… which means stock exchange!). A solitaire ribbon, usually black, could then be incorporated to fasten the bag in place and add decoration to the style.[25] The long ends of the ribbon could even be seen knotted in front of the shirt collar (Fig. 15). Often, much to the ridicule of the rest of society, the Nivernois hat became a firm favourite (Fig. 17). It consisted of a small cocked hat which rested at the top of the wig, regardless of the dizzy heights achieved with the hair . In fact, the ever-growing hairstyles were a big focus for many satirical prints and caricatures and were used in particular to denote exuberance and vanity in men’s fashion during this period.[26]

(Fig. 15) Self Portrait, Richard Cosway, 1770-1775. Met Museum Collections.

(Fig. 16) The St James’s Macaroni, Matthias and Mary Darly, 1772. The British Museum.

(Fig.17) Preposterous Headdresses and Feathered Ladies: Hair, Wigs, Barbers, and Hairdressers, Philip Dawe, 1773. Wikimedia Commons.

Memorable Macaroni Men

As we have touched on earlier, satire is a key part of the Macaroni notoriety.[27] The printers Matthias and Mary Darly, working from their Fleet Street print shop (Fig. 18), specialised in humorous prints of Macaroni Men. Many other printmakers also created satirical prints that ridiculed those that leaned into the Macaroni way of life, but the Darly prints grew to hold a huge amount of acclaim – even with the Macaroni men themselves!

(Fig. 18) A Macaroni Print Shop, Matthias and Mary Darly, 1772. The British Museum.

The men featured in these prints were originally the focus of ridicule and comments on their vanity and extravagance.[28] But, it grew to be something of a status symbol to be printed in one of the Darly prints, which used humorous captions to make it perfectly clear which man was which. Having enough notoriety to be printed proved a Macaroni’s class and legitimacy in being able to afford all the latest European fashions.[29] Of course, this also gave rise to people from lower classes adopting the style to ‘better themselves’ and raise society’s perception of them [30] which, in turn, was the subject of satire.[31]

The people featured in print varied from bankers and politicians, through to artists and botanists, which were all created with clever imagery for identification. For Stephen Fox, a politician in the 18th Century, the satirical print associated with him is of a sleeping man “Dreaming for the good of his country”(Fig. 19). For the banker Alexander Fordyce, a known gambler, his feature in the Darly prints was titled ‘A four-dice Macaroni Gambler’(Fig. 20). This rather cleverly used a graphic representation of four playing dice to be a play on gambling and his name, Fordyce. My favourite depiction of all is of Richard Cosway, who specialised in painting miniature portraits and was known to be rather short in stature. The Darlys concocted ‘The Miniature Macaroni’(Fig. 21) and printed it at half the size of every other Macaroni print!

(Fig. 19) The Sleepy Macaroni, Matthias and Mary Darly, 1772. The British Museum.

(Fig. 20) A (four dice depicted) Macaroni. Gambler, Matthias and Mary Darly, 1772. The British Museum.

(Fig. 21) The Miniature Macaroni, Matthias and Mary Darly, 1772. The British Museum.

To Conclude

As we know from many fashion trends, something initially questioned by many can dilute into common styles for the masses through the choice of colour, silhouette and decoration. The more bourgeoise classes were known to ‘dress up’ more to resemble the fashionable elite by adopting hairstyles or clothing. Macaroni men undoubtedly pushed the boundaries of fashion in terms of what was acceptable to wear and how to behave, especially as it brought into question all manner of questions about class, gender, sexuality and patriotism during a time of great political upheaval.

Despite the satire, prints and publications, our Macaroni friends seem to be consistently less well known than their later successor – the Dandy. But I would argue that they were just as important and potentially more daring. Returning to the Yankee Doodle song that began this research highlights how the media has always been used to mock different social groups, but some seem to have more endurance than others through strains of song or prints in archives. Whilst the reasoning behind the term ‘Macaroni’ in Yankee Doodle has faded into obscurity for many people, the men of this group would have undoubtedly been proud of the legacy they achieved with their daring European fashions. It makes you wonder what other groups have been lost to the mists of time and hope that in future there will be many more people to ‘stick feathers in their caps’ and participate in a multicultural appreciation of fashion… regardless of what anyone else might think!

Clotho Dress Historian, November 7th, 2024.

References:

[1] McCollum, S. (2020) Yankee Doodle the Story behind the Song, Kennedy-center.org. Available at: https://www.kennedy-center.org/education/resources-for-educators/classroom-resources/media-and-interactives/media/music/story-behind-the-song/the-story-behind-the-song/yankee-doodle/ (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[2] Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue: Revised and Corrected, Internet Archive (2014) Internet Archive. Available at: https://archive.org/details/grosesclassical01grosgoog/page/n290/mode/2up?q=yankey (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[3] What was the Grand Tour? (no date) Royal Greenwich Museums Available at: https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/what-was-grand-tour. (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

Meet the Macaronis

[4] Mcneil, P. (2018) Pretty Gentlemen : macaroni men and the eighteenth-century fashion world. New Haven: Yale University Press. Page 19.

[5] Ribeiro, A. (2019) Meet the Macaronis, History Today, Available at: https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/meet-macaronis. (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[6] Swingen, A.L. (2024) ‘Calico Madams and South Sea Cheats: Global Trade, Finance, and Popular Protest in Early Hanoverian England’, Journal of British Studies, 63(1), pp. 114–138. doi:10.1017/jbr.2023.74. (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[7] Mcneil, P. (2018) Pretty Gentlemen : macaroni men and the eighteenth-century fashion world. New Haven: Yale University Press. Pages 30-31.

[8] Johnson, B. (2017) John Bull, symbol of the English and Englishness, Historic UK. Available at: https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/John-Bull/. (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[9] McGirr, Elaine M, Eighteenth century characters: A guide to the literature of the age, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, pg 141

[10] The Social and Political Significance of Macaroni Fashion (1985) Valerie Steele, Costume 19:1, Page 98

[11] Edwards, L. (2020) How To Read A Suit: A Guide To Changing Men’s Fashion From The 17th To The 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Page 62

[12] Mcneil, P. (2018) Pretty Gentlemen: Macaroni Men And The Eighteenth-Century Fashion World. New Haven: Yale University Press. Page 151

[13] Mcneil, P. (2018) Pretty Gentlemen: Macaroni Men And The Eighteenth-Century Fashion World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sartorial Choices

[14] Edwards, L. (2020) How To Read A Suit: A Guide To Changing Men’s Fashion From The 17th To The 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Pages 30-35

[15] Edwards, L. (2020) How To Read A Suit: A Guide To Changing Men’s Fashion From The 17th To The 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Page 63

[16] Lord Algernon Percy (1777/1780) Nga.gov. Available at: https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.43598.html (Accessed: 5 November 2024).

[17] Richard Cumberland - National Portrait Gallery (1776) Available at: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw01669/Richard-Cumberland?search=sp&sText=george+romney&displayNo=60&rNo=4 (Accessed: 5 November 2024).

[18] A Rake’s Progress IV: The Arrest, (1734) Sir John Soane’s Museum Collections Online. Available at: https://collections.soane.org/object-p43 (Accessed: 5 November 2024).

[19] Mcneil, P. (2018) Pretty Gentlemen: Macaroni Men And The Eighteenth-Century Fashion World. New Haven: Yale University Press. Page 41

[20] Ribeiro, A. (2019) Meet the Macaronis, History Today, Available at: https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/meet-macaronis. (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[21] Edwards, L. (2020) How To Read A Suit : A Guide To Changing Men’s Fashion From The 17th To The 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Page 62

[22] Ribeiro, A. (2019) Meet the Macaronis, History Today, Available at: https://www.historytoday.com/miscellanies/meet-macaronis. (Accessed: 3 November 2024).

[23] The Johnston Collection (2019) Macaroni Men, Available at: https://johnstoncollection.org/MACARONI-MEN~68705 (Accessed: 5 November 2024).

[24] Edwards, L. (2020) How To Read A Suit: A Guide To Changing Men’s Fashion From The 17th To The 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Page 62

[25] François Boucher (1996) A History Of Costume In The West. London: Thames And Hudson. Page 452.

[26] The Social and Political Significance of Macaroni Fashion (1985) Valerie Steele, Costume 19:1, Page 102.

Memorable Macaroni Men

[27] The Social and Political Significance of Macaroni Fashion (1985) Valerie Steele, Costume 19:1, Pages 96-98

[28] Style and Satire; Fashion In Print 1776-1925. (2014) Flood, C. and Grant, S. London: Victoria and Albert Museum.

[29] Amelia Faye Rauser - Hair, authenticity, and the self made macaroni - 18th century studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2004, pp. 101-17. Page 112

[20] Edwards, L. (2020) How To Read A Suit: A Guide To Changing Men’s Fashion From The 17th To The 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts. Page 62

[31] The Fish-Street Macaroni (1772) James Bretherton. Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1138744/the-fish-street-macaroni-print-bretherton-james/